For some years I have been studying the history of rum, and in particular its origins. The results of this research are to be found in my articles published in “Got Rum?” magazine, and in some websites about rum. Many articles were about Great Britain and  the British Empire, owing to the early, massive diffusion of rum among British people. The very word Rum is generally held to be English, even though its origins are uncertain.

the British Empire, owing to the early, massive diffusion of rum among British people. The very word Rum is generally held to be English, even though its origins are uncertain.

But, around 2014, while I was studying the history of British rum, I came to realize with astonishment the enormous importance that rum had in Early America. More, the very birth of the new American Republic was dripping in rum. As a matter of fact, colonials drank a lot. And they drank mainly rum. Rum was not only a very popular commodity, but a lubricant of social life. Taverns were the focus of political and social life and in taverns most people drank, first of all, rum. And rum was present in all the rituals which mark life: births, weddings, all kinds of festivals and celebrations, funerals. North American colonists imported great quantities of rum from the West Indies, but I discovered that they were also great producers of it.

In the British Colonies of North America, rum was so important that, as money was scarce, rum often replaced it as currency and the real indicator of the value of goods. Rum is also generally thought to have played a pivotal role in the infamous slave trade which enriched the new nation and in the subjugation and destruction of American Indians. And above all sugar, molasses and rum are largely considered among the real reasons of the rebellion of the American colonists against their homeland. Therefore it is not without a reason that it has often been written that rum is the real Spirit of 1776. All this, I was saying, kindled my interest in the role that rum played in the birth of the United States.

At the same time, I had become aware that something extremely interesting was happening in the US around rum.

First of all, for some years rum had been produced again in the US, after a long period of neglect. There were already hundreds of rum distilleries in the US. They were usually small craft enterprises, with a strong territorial bond, which often used locally grown sugar cane. New ones were starting, month after month. Each of them produced small quantities, but all together they already represented a considerable, and ever growing, proportion of rum consumption in the US. It was also evident that there was a substantial growth in the sales of quality rums, with higher prices, the so called Premium Sector, and I think the two things are connected.

This in itself is of great interest to the rum enthusiast. But as a historian I am truly impressed also by the political demands of many of these small producers. To put it simply, and I apologize to them and to the readers for this oversimplification, American small producers of rum come up against the great multinationals and ask for lower taxation and greater freedom of enterprise. And their pressure is growing. And all these trends are increasing day by day.

In short, prompted by the importance that rum had in the past, and the renewed importance it has in the present, I became convinced that the history of rum in early America, from the first settlers until the decline of rum and the surge of whiskey around 1830 in the United States, deserved a book. So, I decided to write that book.

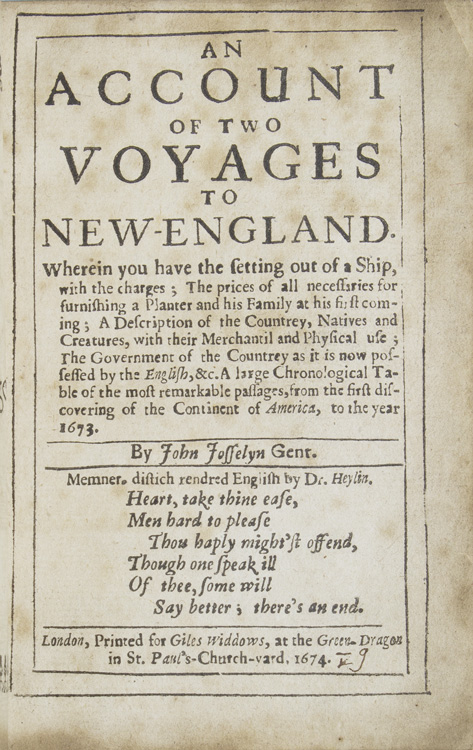

A warning. As my readers will see, I have devoted many pages to Boston and New England, both for the unquestionable importance of Boston in the history of American rum and for the quantity, the quality and the availability of the sources. If, by reading this book and finding the gaps in its scope, others will be encouraged to carry out more extensive research about the history of rum in the other Colonies, I will be extremely happy.

Marco Pierini