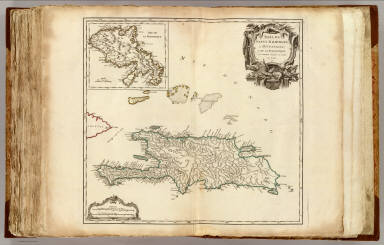

In the three articles already published in this series, we have seen that, according to some contemporary sources, commercial production of rum may have begun in Saint-Christophe, Martinique and other French islands a few years before it got going in British Barbados. Moreover, we have also seen that when the French began to settle in the Caribbean in the 1620s and 1630s, they knew America and its resources well, and that a true distilling industry had been well-established in France for some time.

Now, I wish to go back to a number of contemporary French sources.

The Capuchin friar Hyacinthe de Caen came to Saint-Christophe in 1633 with a brother friar following Pierre d’Esnambuc, the founder of the colony, and participated in the early colonization of Martinique in 1635. He later met Dominican missionary Raymond Breton, the great anthropologist and ethnologist, author of the first Caribbean-French dictionary; he went back to France some years later, and then returned to the Caribbean. He and other brothers of his order clashed with the local authorities in Saint-Christophe, and he was arrested and expelled from the island in 1646. He went ashore in Guadalupe with another friar, and nothing further was heard of them.

In 1641, de Caen wrote his “Relation des îles de Saint-Christophe, Gardelouppe et la Martinique…”, which was not published until the year 1932. In this work we may read:

“Les cannes à sucre y étant cultivées, il y avra plus grande occupation à faire les sucres, principalement dans les îles de la Gardelouppe ou la Martinique, qui pourront un jour fournir la France …” That is, more or less:

“As sugarcane is cultivated in this place, there will be plenty of work making sugar, primarily on the islands of Guadeloupe and Martinique, that will one day be able to supply France …”

So sugarcane was already being grown on the islands, and grew well there, in 1641.

Following a lengthy description of cassava, the ouïcou that was made from it and its uses, de Caen then wrote: “De ce breuvage, se fait encore de l’eau-de-vie propre pour le pays …” that is, “From this beverage, they even make their own water of life in the country…”, while, he wrote, it was impossible to grow grapevines there.

Sugarcane was therefore already being grown on the French islands of the Caribbean in 1641, but not grapevines, and wine had to be imported. So what was the brùle-ventre which, according to Buton, the slaves made much use of; a distillate of ouïcou ? We don’t know.

Now, let us reread, in view of the above, a passage from Maurile de Saint-Michel’s “Voyage des Isles Camercanes en l’Amérique”, published in 1652:

“Never before have I seen a country where sometimes more diverse kinds of beverages can be found than on S. Christophe: more ancient and longer Frenchified than Martinique; as the Dutch bring their beer there; the Normans their cider, but it does not keep for long; those from S. Malo stop in Madeira and collect the wine which they carry and sell at a hefty price; those from La Rochelle the wine from Gascony which ages and becomes sour very soon; but vinegar sells well; everybody works hard to get water of life to the island, and that is the lifeblood of this country. Some send there [water of life] from rosolio; others produce it from sugarcane wine, and I will soon tell you how it is produced; others from Oüicou; others from Masbi.”

In 1652 the islanders were therefore already distilling sugarcane wine to make rum, and also distilled Oüicou and Masbi, that is, fermented beverages the natives traditionally made from cassava and potatoes. This was not an isolated case, but widespread practice. As F.H. Smith writes in “Caribbean Rum” (2005), “Before the large-scale transition to sugar production in the 1640s, colonists in the Caribbean experimented with the alcoholic potential of various local plants. … Distilling immediately became a central element of the French Caribbean sugar industry. In 1644, Benjamin Da Costa, a Dutch Jew from Brazil, introduced sugar making equipment and, perhaps, the first alembics, into Martinique. Yet, a manuscript from Martinique dated 1640 when the colony was only five years old, stated, ‘the slaves are fond of a strong eau de vie that they call brùle ventre [stomach burner]’. Although brùle ventre sometimes referred to French brandy, the comparative use of the term hints at a locally made concoction other than imported brandy. In the context of the Caribbean, brùle ventre was likely a distilled sugarcane-based alcoholic beverage and suggested that rum distilling preceded Da Costa’s arrival in 1644.”

Now here is a hypothesis which I cannot prove, but wish to propose anyway: in the early years of French (and British) colonization of the Caribbean, the number of European colonists and African slaves was limited, while the indigenous population was numerous. So the best way to get strong drink cheap would have been to distil ouïcou and other fermented beverages traditionally made by indigenous peoples. Later, however, the number of French colonists and, especially, the number of slaves grew rapidly, while the indigenous population continued to drop as an effect of war, disease and other factors. This may have been one of the factors that led the colonists to ferment and distil the by-products of sugarcane, which was by now widely grown, to obtain an abundant, cheap spirit.

But now let us return to Maurile de Saint-Michel. After describing how sugar is made, he writes: “Quand aux cannes rongées par les rats; ausquels Monsieur le General donne la chasse tant qu’ il peut, avec ses chiés; on en fait un breuvage, qu’ils nommèr Vin de canne; … Monsieur le General en faict remplir des pippes, & en retire grand profit, en les faisant vendre és magazins. Il est plus aggreable à boire, qu ‘il n’est sain.” That is, “When the canes have been gnawed by mice, which the General hunts as much as he can with his dogs, a beverage is made from them, referred to as cane wine … The General has barrels filled with it, and he earns a great profit from it, having it sold in the shops. It is more pleasurable than healthy to drink.”

And so Martinique was not exempt from the plague of mice! These words are reminiscent of Richard Ligon’s description of Barbados. Mice were most likely not native to the islands but brought over on European ships. They had few natural enemies in the Caribbean, and the sugarcane plantations offered them a virtually limitless amount of food. All the sources of the day report that mice were very numerous, infesting the colonists’ homes and plantations, a true plague. The problem was so serious there were slaves whose work consisted entirely of hunting them, who were rewarded a bottle of rum for every 50 mice they killed.

It is clear that in the French islands, as in Barbados, the production of alcoholic beverages made from sugarcane gave rise to an economically significant trade. And it would appear that in order to make this drink, which we now call rum, the people of the French islands used the worst quality cane, gnawed by mice, and not the skimmings of the cauldrons as in Barbados.

And now allow me a historic digression not strictly linked with rum. The history of the British colonization of the Americas is by far better known than the simultaneous French colonisation. And many of the authors who have published important works on British colonisation tend, whether consciously or not, to treat it as a unique phenomenon. Yet the two colonial enterprises were very similar, as were the societies they created in the Caribbean.

The French and the British were both looking for the same thing: tropical products that would allow them to get rich quickly. Some of the colonists did get rich, even very rich, but the majority of them had very hard lives, and the mortality rate was high for all. They even had similar tastes; both, for example, loved pineapple.

The French and the British also faced the same problems. They had to deal with an alien and often hostile natural world; they suffered the devastation of hurricanes and earthquakes; and they suffered from horrible new diseases and an oppressive climate.

What’s more, they were living in a state of permanent war: English and French fought each other, and both fought the Spanish, the pirates and the Carib. Even during rare times of peace, the rich feared the mass of indentured servants, and all the whites feared a revolt of the increasingly numerous slaves.

To escape from this hell on earth, both English and French settlers sought oblivion in alcohol. When Maurile de Saint-Michel writes “Never before have I seen a country where sometimes more diverse kinds of beverages can be found than on S. Christophe”, we are reminded of Richard Ligon, who, in his much better-known “A True and Exact History of the Island of Barbados”, tells us how much the British plantation owners in Barbados drank.

In short, the French colonisation of the Americas was much like the British one. With one important difference: in numbers. According to Philip P. Boucher, in his seminal “FRANCE AND THE AMERICAN TROPICS TO 1700. Tropics of Discontent” (2008), “French migration across the Atlantic in the early modern era was comparatively small. Global estimates suggest a figure of 60,000 to 100,000 leaving for the Americas in the years 1500-1760, as compared to 746,000 British subjects, 678,000 Spaniards, and even 523,000 from thinly populated Portugal. France at the same time had the largest population by far of any European state, some eighteen to twenty million. Only the Dutch, with some 20,000 migrants, trailed France among the big five imperial powers.”

And the low number of settlers may have been the structural weakness in the French colonization of the Americas.

Marco Pierini

PS: I published this article on February 2019 in the “Got Rum?” magazine. If you want to read my articles and to be constantly updated about the rum world, visit www.gotrum.com