In the previous articles, we tried to tell how Rum conquered the British mind and market in the 1700s, one of the greatest and most successful marketing campaigns of known History. We saw how it was the result of a real lobbying effort made by the West Indies’ interests with the help of Science, Fashion and the Royal Navy. According to S.W. Mintz in “Sweetness and Power” it was an example of “much-needed creeping socialism for an infant industry”.

To complete the frame of this public effort to promote Rum consumption, we now want to tell about the diffusion of Rum in the British Army in the 1700s and early 1800s, which R.N. Buckley in “The British Army in the West Indies” called “state-sponsored alcoholism”.

Traditionally, English soldiers had beer, and sometimes wine, as customary ration. The Army did not have the problem of the Navy to maintain water and beer drinkable during the long oceanic voyages, so it did not need to introduce spirits so soon.

Large distribution of Rum to soldiers began round the mid of the 1700s in the West Indies and North America, and increased rapidly during the century. Yet during the French and Indian War (1754 – 1763) Rum was distributed only on special occasions, for instance when men had to deal with bad weather and/or fatigue, but it was not a daily allowance. Only during the American Revolution (1775 – 1783) do we know about a regular allowance of Rum: a gill daily, which amounts to a gallon per month.

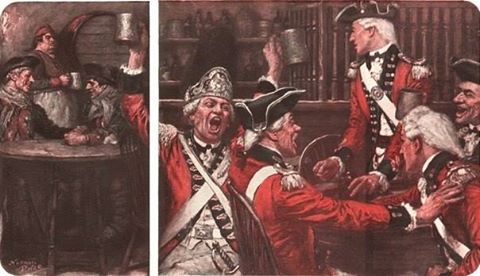

But in America, Rum was cheap and easy to buy in large quantities. Licensed sutlers, unlicensed ones, soldiers’ wives, planters, and often the officers themselves sold cheap Rum to the soldiers. And soldiers bought and drank it in huge quantities with uncontrollable frenzy. They drank such quantities that probably they spent most of the time in a state of near inebriation.

Why? The 1700s in Britain was an age of hard drinking, see the so-called “Gin Craze”. Moreover, a soldier’s life was both brutal and boring. Fatal diseases scourged them. Short periods of battle with its exertion and bloodshed , were succeeded by long periods of emptiness and idleness. Getting drunk was often the only escape available. Wine and brandy were expensive, too much for ordinary soldiers, while Rum was affordable, and in great quantity. Rum, therefore, was their usual drink, their cheap Stairway to Heaven.

Drunkenness worsened the already poor health of the soldiers, with negative consequences on the efficiency of the Army. It also undermined discipline and strained the relations with civilians, with discontent, floggings and court- martials. Many officers and military surgeons were well aware of the dangers of this situation, but they were not able to stop it.

The fact was, soldiers wanted to drink. Better, they wanted to get drunk in the quickest and cheapest way possible. Therefore, to distribute Rum was the easiest and cheapest way to have their allegiance and diligence. The officers knew that to try cutting or also just limiting Rum allowances could bring troubles and also open mutiny. Then, alcohol had deep roots in military culture.

Medicine was also ambivalent: many doctors condemned the abuse of alcohol, but others considered it useful to preserve men’s health in both cold or hot weather and “as a precaution against the noxious air”. Last, when out of duty, troops usually did not live in military barracks, but were billeted in taverns and civilians’ houses where control was impossible and Rum easily available.

So, drunkenness was common in the British Army well into the 1800s. What kind of Rum did they drink, though? Let’s see.

John Bell served as a military surgeon in Jamaica. Back to England, in 1791 he published An Inquiry into the causes which produce, and the means of preventing diseases among British Officers, Soldiers, and others in the West Indies. Containing observations on the action of spirituous liquors on the Human body. As many, Bell was shocked by the mortality rate “in some of those regiments, two thirds, and in others upward of a half, died, or were rendered unfit for service before they had been a year, or at most a year and a half, in the island of Jamaica.” Actually, in the West Indies the diseases – the “fevers” – killed many more soldiers than the enemy’s weapons.

Like many doctors of the time, Bell underestimated the role of infectious diseases and thought that climate, diet and life-style were the main factors warranting good health. In his opinion, the excessive daily consumption of Rum was the primary cause of illness and death among the soldiers. The daily allowance was half a pint and was usually diluted with water, we do not know in what ratio. But soldiers bought much more undiluted Rum, “large quantities of which of the most execrable quality” from private sellers at a cheap price.

Bell didn’t approve of the addition of water to Rum. “In this mode of using it, Rum is perhaps more injurious to the body than any other, because it makes only a simple uncompounded impression, which becomes weaker by a frequent repetition of its cause: and therefore, after some time, an increase of the quantity of spirit becomes necessary.” In other words, the daily allowance of Army diluted Rum paved the way for alcoholism.

This is not all. Distillation is an art, but a dangerous one, even today. Two centuries ago, in the West Indies, planters and distillers produced for the soldiers a kind of Rum that only needed to be strong and cheap. It was fermented and distilled very quickly, saving on costs, without any aging or regard for quality. As far as we know, the heads and the tails were not removed and in all likelihood in Rum there was methanol, fused oils and bad congeners. And lead powder too. Yes, because at the time lead and pewter were largely used in sugar and Rum-making machinery.

We know of soldiers who died immediately after they had drunk. Or who fell to the ground in a state of torpor. Of hardy young men who declined rapidly. Of excruciating pains, ulcerated organs, illnesses … . The reports of the military surgeons of the time, and the first scientific post-mortems, tell us a terrifying story.

To sum up, it seems that soldiers’ Rum was not only the “hot, hellish and terrible liquor” described by Richard Ligon in the 1650s, it was often actually a toxic beverage.

Marco Pierini