Even though

Brazil is its birthplace, in order to conquer the world rum had to leave Brazil

and go and grow upin the Caribbean,

particularly in Barbados. And the voyage from Brazil to Barbados made a new

detour to Holland.

In Brazil,

with the so called “War of Divine Liberation” that began in Pernambuco in 1645,

the Portuguese made up the lost ground and finally forced the Dutch out of

Brazil in 1654. Some of them relocated to Barbados and Martinique.

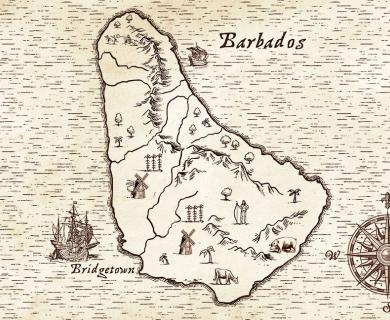

Barbados is a

small island. It is 34 kilometers long and 23 kilometers wide at its widest,

for a total of a little more than 430 square kilometers It’s the easternmost of

the Lesser Antilles. It’s low and flat and not easy to sight, but due to the

prevailing winds it was often the first island which ships sailing from Europe

came upon. It’s an independent country, a member of the British Commonwealth.

But let us look into the history of its colonization from the very beginning.

“Some Dutch

vessels, which were specially licensed by the court of Spain to trade to

Brazil, landed in Barbados on their return to Europe, for the purpose of

procuring refreshment. On their arrival in Zeeland they gave a flattery account

of the island, which was communicated by a correspondent to Sir William

Courteen, a merchant of London, who was at that time deeply engaged in the

trade with the New World”. Thus R.H.Schomburk writes in his “History of Barbados” published in London

in 1847, and then he adds:

“It is

asserted that previous to the revolution the Dutch possessed more interest in

the island than the English, which they gained by their liberal spirit in

commercial transactions.”

(The “revolution”

is the English Civil War). Not all modern historians entirely agree with

Shomburk and some maintain that the role of the Dutch was more limited. Anyway,

the English settled there in 1627 and the first voyage was funded by that very

Sir William Courteen.

They were

looking for a tropical land where to grow some lucrative crops. They tried

cotton, tobacco and other crops, but with little success. Then they tried

sugarcane cultivation. The English colonists did not possess the technical

knowledge necessary to grow sugarcane and then produce sugar in an efficient,

profitable way, so for “two or three years”

their attempts had extremely poor results.

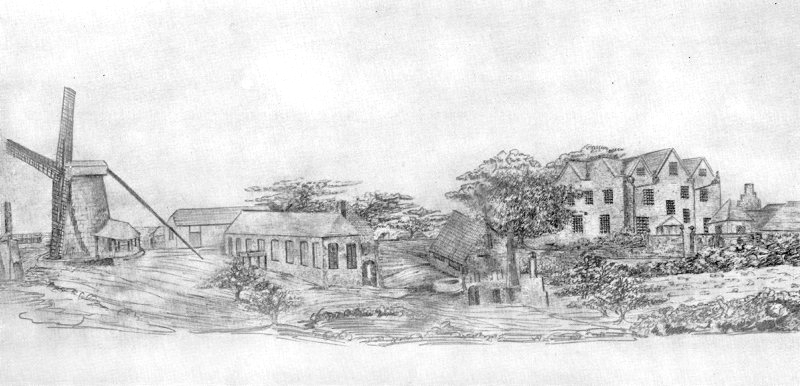

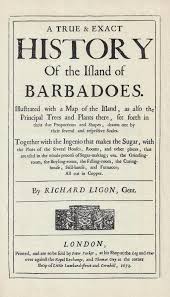

In 1647

Richard Ligon, a Cavalier, a Royalist, ruined by the Civil War, left England

and sailed to Barbados to seek his fortune. He will spend 3 years there. Back

in England, he will write a book on his journey, “A true and Exact History of the island of Barbados”. This book,

published in 1657, is (possibly) the first true mention of the existence of rum

in the English language, even though it was not called rum yet. Here it is:

“We are seldom dry or thirsty, unless we

overheat our bodies with extraordinary labor, or drinking strong drinks; as of

our English spirits, which we carry over, or the French Brandy, or the drink of

the Island, which is made of the skimmings of the coppers, that boil the Sugar,

which they call Kill-Devil”.

Kill-Devil is

therefore the first name under which rum enters English language.

Later in his

book, Ligon writes:

“The seventh sort of drink is that we make of

the skimming of sugar, which is infinitely strong, but not very pleasant in taste;

it is common and therefore the less esteemed; the value of it is half a Crown a

gallon, the people drink much of it, indeed too much; for it often lays them

asleep on the ground, and that is accounted a very unwholesome lodging.”

And more:

“This drink has the virtues to cure and

refresh the poor Negroes, whom we ought to have a special care of, by the labor

of whose hands our profit is brought in […] It is helpful to our Christian

Servants too; for, when their spirits are exhausted by their hard labor, and

sweating in the Sun, ten hours every day, they find their stomach debilitated

and much weakened in their vigor every day, a dram or two of this Spirit is a

great comfort and refreshing.”

But before

going on with the “drink of the island”, let’s see what Ligon writes about

sugarcane:

“At the time we landed on this island, which

was in the beginnings of September 1647, we were informed, partly by those

Planters we found there, and partly by our own observation, that the great

works of Sugar-making was but newly practiced by the inhabitants there. Some of

the most industrious men, having gotten plants from Pernambuco, a place in

Brazil, and made trial of them at the Barbados; and finding them to grow, they

planted more and more, as they grew and multiplied on the place, till they had

such a considerable number, as they were worth the while to set up a very small

Ingenio, and so make trial what Sugar could be made upon that soil. But, the

secrets of the work being not well understood, the Sugars they made were very

inconsiderable, and little worth, for two or three years. But they finding

their errors by their daily practice began a little to mend; and, by new

directions from Brazil, sometimes by strangers […] were content sometimes to

make a voyage thither, to improve their knowledge in a thing they so much

desired. […] And so returning with most Plants, and better Knowledge, they

went on upon fresh hopes, but still short, of what they should be more skillful

in: for, at our arrival there, we found them ignorant in three main points,

that much conduced to the work […] But about the time I left the Island,

which was in 1650 they were much bettered …”

To make room

for sugarcane, forests were cut down and other crops were abandoned. But this

took labor force, and plenty of it. The cultivation of cane is extremely hard

work. First the cutting, appalling toil, under the sun, with tight labor times

to take advantage of the short period in which the sugar content is at its

highest. Then the cane has to be crushed quickly. Again hard work, and

dangerous too. Finally, the juice has to be boiled several times in great

coppers, in a scorching tropical climate.

In the first

decades, most of the labor force was made up of indentured servants, that is,

contract-bound servants. They were poor English citizens who, in the hope of a

better life, tried their luck in the colonies. But they had to get there, and

travel costs were high. So these poor wretches agreed to give up their freedom

and to serve a master for a certain period of time, usually 5 years, in

exchange for transport, accommodation and a small final sum, which would allow

them to set up their own business. Once the contract had been signed – because

it was a proper legal contract – the master could use them as he pleased, treat

them as he pleased and even sell them to others. Sometimes they were even

recruited by force.

There was

also a minority of black slaves bought in Africa. Over the next decades,

though, things changed. The white servants left the island as soon as they

could and fewer and fewer came to replace them, so planters had more recourse

to slaves. Today, the great majority of the inhabitants of Barbados are of

African origin.

Then,

according to Ligon, British settlers in Barbados learned the know-how of sugar

in Dutch Brazil. And we know that in Brazil they commonly produced rum.

Therefore, it makes sense to think that in Brazil they also learnt the art of

the distillation of the by-products of sugar to produce rum.Ligon lived in Barbados from 1647 to

1650 and he noted that all the important sugar plantations already had their

own distillery and some skilled workers and that rum represented a relevant

integration of the planters’ income. They used it for the consumption of their

black slaves and white servants and also sold it on the island and abroad. So,

as early as 1650 in Barbados rum was currently produced, consumed and sold. It

was a very strong, not pleasant-tasting spirit. It was cheap and was drunk in

great quantities by the lower classes. It could be harmful, but at the same

time it was thought to have healthy qualities too. And it was already

economically relevant.

The origin of

the word “rum” is uncertain, but as far as we know, it was used for the first

time right in Barbados. In 1652 (or 1651) a much quoted visitor wrote:

“the chief fuddling they make in the island

is Rumbillion, alias Kill.Divil, and this is made from sugar cane distilled, a hot, hellish, and

terrible liquor.”

And some

years later it finally appeared in a deed for the sale of Three Houses

Plantation recorded in Barbados in 1658, where we can read: “four large mastrick cisterns for liquor for

Rum”.

Marco Pierini

PS: if you are interested in

reading a comprehensive history of rum in the United States I published a book

on this topic, “AMERICAN RUM A Short

History of Rum in Early America”. You can find it on Amazon.