One of the most common mistakes among contemporaries is the deep, often unconscious belief that the world has started today, or yesterday at the latest. What I mean is, the belief that many of the phenomena we see in our world are completely new, never seen before. That is the case, for example, in the modern obsession with wellness, body care, health etc. We think this is something new, a mania of our rich and affluent society, unknown in the past, which was poorer, rougher and only mindful of the basic things of life. Well, this is not true.

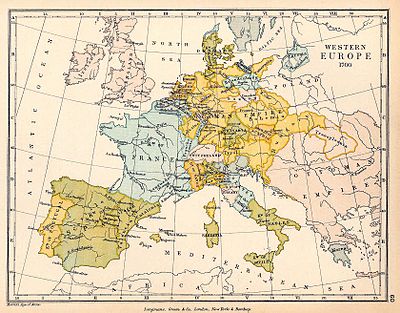

XVIII century Britain was rich and powerful. No important political or economic perils threatened it. And, like today, good society was very worried about wellness and health, both of body and mind. Modern scientific medicine was only beginning and the air, the climate, food, drinks, habits were being studied with great commitment to protect and improve people’s health and well-being. For example, it is in this century that spa treatments and the use of sea bathing for therapeutic purposes became widespread.

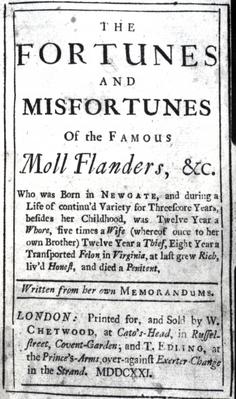

The first Italian distillers of the XIII century called the spirit they produced aqua vitae, water of life, beca

use they believed it was a panacea for many ills and since then the links between spirits and wealth in European culture have always been

strong. I don’t know much about the history of medicine, but I think that their belief had a real basis. As we know, alcohol is an antisepti

c and it is reasonable to think that the sick people to whom aqua vitae was administered had health benefits, even though at the time the existence of microbes was unknown. For centuries, in Europe and then in the American colonies there was a widespread persuasion that distilled beverages were nourishing and healthy.

In the XVIII century the surge of new, scientific medicine started to undermine the confidence in the health-giving properties of alcohol and some doctors began to advise against the perils of spirits abuse. The temperance movement moved its first steps.

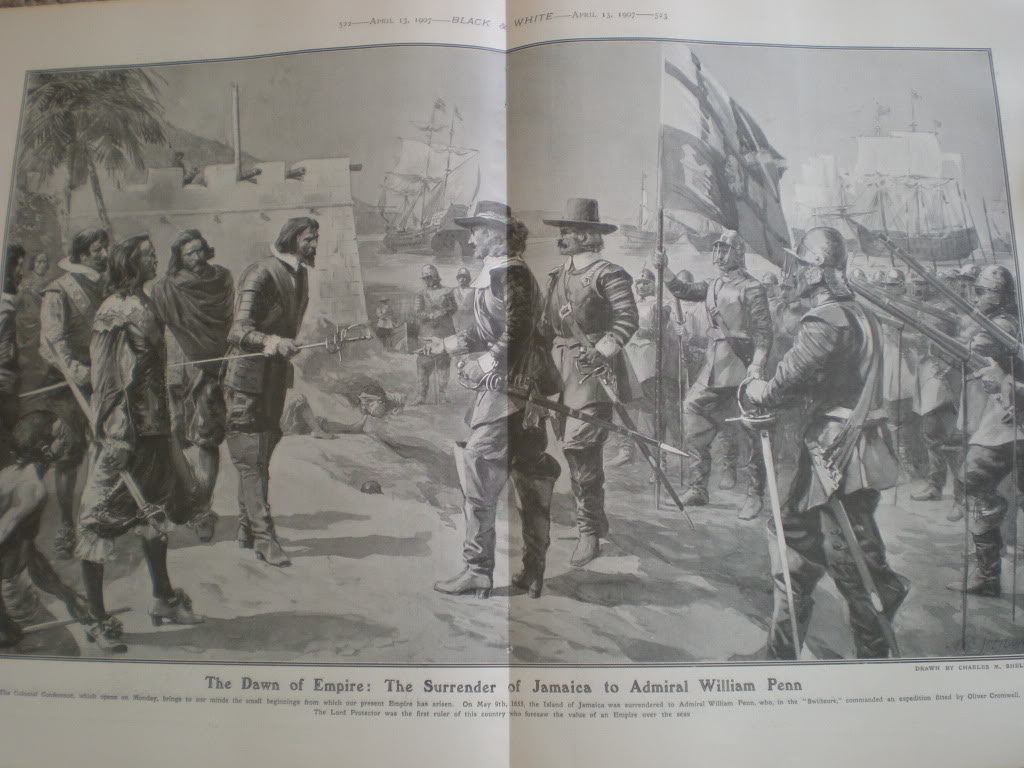

Therefore, in order to spur the consumption of rum, it was necessary to present it as something healthy and useful for the well-being of the people. Even better if it was possible to ease the burden of the new-found diffidence towards spirits o

n its competitors which, in the Great Britain of the time, were mainly two: brandy among the upper classes, and gin among the lower ones. And both of them were targeted.

As early as 1690 a Dalby Thomas, an advocate for British Caribbean sugar interests, writes: “ [Rum is] wholesomer for the Body, which is observed by the long living of those in the Collonies that are great Drinkers of Rum, which is the Spirits we made of Molasses, and the short living of those that are great Drinkers of Brandy in those parts.”

And even in 1770 when rum imports had been surpassing brandy ones for decades, a Robert Dossie, physician, wrote: “

The drinking of Rum in moderation is more salutary, and in excess much less hurtful, than the drinking of Brandy” Pages and pages of medical evidence, chemical dissertations, pseudo-scientific experiments followed.

Gin was an easier target. It was a dangerous competitor for bread in the use of the precious grain and its huge diffusion among the poor was a major social problem of the time, to the point that towards the end of the century Parliament intervened with prohibitions and limitations that greatly reduced both production and consumption. But to rum advocates it was not enough. It was necessary to reaffirm that gin was hurtful to the health and at the same time persuade English people with “scientific” arguments that rum was not harmful, quite the contrary, it could be beneficial to hu

man health. So, in 1760 an anonymous wrote:

“Since the Suppression of Gin the Consumption of Rum has been greatly increased, and yet Dram Drunkenness, with all its dreadful Effects, has entirely ceased.” And later he goes on: “Gin is vastly more destructive to the Human Frame than the Sugar Spirit.”

Then, our author prescribes rum as a cure for lack of appetite and other illnesses, maintaining that rum is highly recommended for “weak and depraved appetites and Digestions, an

d in many other Distempers of the declining sort” and, after citing long recommendations of authoritative doctors, he concludes: “Gin is a Spirit too fiery, acrid, and inflameing for inward Use – But … Rum is a Spirit so mild, balsamic, and benign, that it its properly used and attempered it may be made highly useful, both for the Relief and Regalement of Human Nature.”

So, with a little help from its friends, rum began to conquer the minds and the throats of British people.