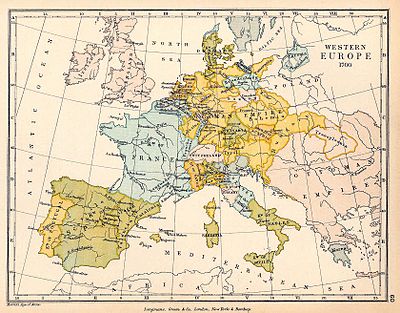

Between 1689 (beginning of the so-called King William’s War) and 1815 (final defeat of Napoleonic France), England / Great Britain and France fought each other in a long series of wars which, according to some historians, were merely phases of one long conflict for supremacy in Europe and all over the world. In this context, the foreign policy of Great Britain had two fundamental objectives: to defend and expand its colonial and commercial empire and to maintain the balance of power among the many States of Europe, so that none of them could be strong enough to dominate the whole continent.

Great Britain had two fundamental objectives: to defend and expand its colonial and commercial empire and to maintain the balance of power among the many States of Europe, so that none of them could be strong enough to dominate the whole continent.

It became therefore increasingly intolerable for the British to finance France, and its ally, Spain, through the massive imports of wine and brandy. Regarding wine, an alternative was quickly found. Trade agreements were signed with Portugal, and Portuguese wine replaced French wine to a large extent, thanks also to the British fondness for sweet wines. But brandy was a hard nut to crack. The English upper classes loved it and didn’t want to do without it.

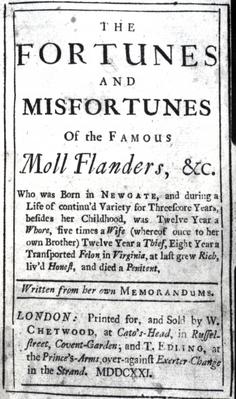

And then rum arrived. It was entirely produced in the British colonies by British labor and capital, and transported to the Mother Country by British ships, so the wealth spent to buy it stayed at home. It was therefore the perfect beverage to replace brandy. But the English upper classes, the better sort, were not acquainted with it, and its consumption, at the beginning of the century, was still almost non-existent, to the point that Daniel Defoe, in his Moll Flanders published in London as late as 1722, when relating an episode in the life of his heroine, feels obliged to explain to his English readers what rum is: “However, I called a servant, and got him a little glass of rum (which is the usual dram of that country), for he was just fainting away”

Moreover, the upper classes did not consider it suitable for themselves: it was rough, not refined enough and anyway it was too cheap. It was necessary to get the people used to drinking rum, and, at the same time, to improve its image in order to make it worthy of the upper classes. It did not seem an easy undertaking, but the lobby of the West Indies planters, the Parliament, the Government and British officials in general joined forces to devise what today we would call a massive promotional campaign to boost rum consumption. And they were extremely successful.

Here are some figures:

in 1697 England and Wales imported (legally) only 22 gallons of rum. In 1710 the gallons were already 22.000 and in 1733 500.000! As of 1741, rum imports regularly overtook those of brandy.

How did they do that?

the British Empire, owing to the early, massive diffusion of rum among British people. The very word Rum is generally held to be English, even though its origins are uncertain.

the British Empire, owing to the early, massive diffusion of rum among British people. The very word Rum is generally held to be English, even though its origins are uncertain.