The very word alcohol derives from the Arabic al–koél (where al– is the article), but it had a different meaning. In Arabic it indicated the extremely fine, impalpable powder of antimony that, mixed with water, had been used since ancient times in the Orient, especially by women, to paint their eyebrows, eyelashes and the edge of the eyelids black. The name and the thing itself entered the West thanks to the translation into Latin of Arabic books. In Spagna, dove la presenza e l’influenza araba è stata forte, sia il nome che la cosa sono state comunemente usate fino al XVI secolo, ed il verbo, alcoholar, ormai in disuso, significa ancora “colorarsi gli occhi di nero”.

“Alcohol was called by Arabic chemists such as Ibn Badis (11th century) خمر مصعّد (distilled wine). The current word for distilled wine in Arab Lands is `araq عرق which means sweat. The droplets of ascending wine vapours that condense on the sides of the cucurbit are similar to the drops of sweat.” (Ahmad Y. al-Hassan) And I suppose that from `araq come also raki, arrack etc.

So, where does our use of the word alcohol come from? As far as I know, it comes from the famous physician, alchemist and astrologer Teophrastus Paracelsus (1493-1541). Paracelsus used this word to indicate the spirit of wine, which he called alcohol vini, wine alcohol, since it was the quintessence, the noblest and most essential part of wine. This new name gradually passed on to chemists and physicians, who ended up omitting vini and thus the word alcohol remained.

But what exactly was the role of the Arabs in the origin of Spirits? Let’s see.

First of all, “If we speak of Arabs in this chapter, we include all those that belong to the civilization of Islam, which means Syrians, Persians, Copts, Berbers and others too. As early as one century after the death of Muhammed (632 A.D.) a large world empire has arisen from a local Arabian movement, and its center is transferred to Syria, and later Mesopotamia. The Islam knocks at the doors of Byzantium and menaces Italy and France.” (Forbes)

The Arabs read and translated the works of the Greek and Hellenistic culture, annotated them and preserved them, kept them alive within their culture. Those first centuries are the Golden Age of Arab civilization. From Spain to Central Asia peoples and states shared the same (high) culture, with many thriving academies and centers of studies supported by enlightened monarchs. One of the reasons of this success was the Arabs’ religious tolerance. Even before the arrival of the Arabs the old Academy of Athens founded by Plato had been closed (529 A.D.) and many Greek heathens had moved to the hospitable cities of Iran. Later the Byzantine Empire was deeply divided by theological disputes and many suffered bloody persecutions, so many a group of “heretics” settled in the Arabian Empire. For instance, the Nestorians settled mostly in Persia, now Iran, and in present-day Iraq. Many Jewish scientific centers were situated in the Arabian Empire too.

In chemical technology too we owe much to the Arabs. For instance, glass and pottery industries made it possible to make better vessels and containers for distillation technique and thus also made new experiments possible to chemists. Pharmacy and other branches of medicine could flourish. Often the Arabian chemists were also inclined to consider distillation an important process for agricultural industry. In their hands the distillation of rose-water, vinegar, rose-oil and other perfumes and essential oils grew to become a true industry and rose-water was sent all over the world. Clearly, the perfume and cosmetics industry was a flourishing one, reflecting a better quality of life. It is important to remember that the cultural renaissance of the West in the early centuries after the year one thousand AD owes much to the Latin translation of Arabic texts and of Greek texts previously translated into Arabic.

But let’s get to alcoholic distillation. Forbes is clear: “It will facilitate our discussion of these works if we state beforehand that no proof was ever found that the Arabs knew alcohol or any mineral acid in the period before they were discovered in Italy …” Later, writing about the great Arab alchemists till 1200, he states “All these authors describe the same apparatus, which was incapable of distilling low-boiling substances. As none of them ever mentions alcohol it is practically certain that this substance was unknown to the Arab world” till the XIV century when the introduction of the new Western type of distilling apparatus enabled chemists to recover low boiling distillates.

Contemporary Arab authors claim the opposite, though.

According to Ahmad Y. al-Hassan in his online article Alcohol and the Distillation of Wine in Arabic Sources From the Eighth Century Onwards “The distillation of wine and the properties of alcohol were known to Islamic chemists from the eighth century. The prohibition of wine in Islam did not mean that wine was not produced or consumed or that Arab alchemists did not subject it to their distillation processes. Jabir ibn Hayyan described a cooling technique which can be applied to the distillation of alcohol. Some historians of chemistry and technology assumed that Arab chemists did not know the distillation of wine because these historians were not aware of the existence of Arabic texts to this effect. … the art of distillation of spirits is credited to the Arabs especially the Arabs of al-Andalus.”

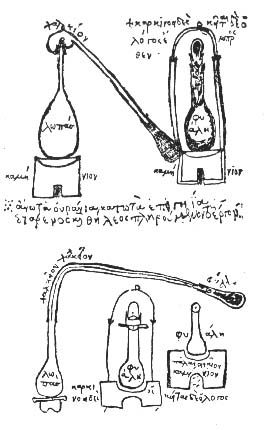

Arabic manuscript showing the distillation process in a treatise of chemistry. © The British Library, London.

Ahmad Y. al-Hassan and Donald R. Hill in “ISLAMIC TECHNOLOGY An illustrated history” quote directly a passage by Al-Jabir [known in Latin Europe as Geber] “And fire burns on the mouth of the bottles [due to] … boiled wine and salt, and similar things with nice characteristics which are thought to be of little use, these are of great significance in these sciences “

And later in their book, they write “The Muslims are credited with the development of the distillation apparatus classically known in chemistry as the retort, but also called the ‘pelican’ or ‘cucurbit’ because of its bird-like or gourd-like shape. In this case the still-head ceased to be a separate entity and better cooling resulting in the collection of an increased amount of distillate came about of itself if the side-tube were made long enough.”

About cooling, the authors admit that early “Arabic manuscripts do not show any water-cooling sleeve round the side-tube. Nevertheless, it seems to have been appreciated that cooling the tube would improve condensation of the vapors, and sponges, cloth or rags periodically moistened with cold water were placed round the top of the still. On present evidence it is usually suggested that the use of cooling water was a later development that occurred in the West. At the same time, a word of caution is needed because though the distillation of alcohol requires external cooling of the retort or of the side-tube, our present knowledge of Arabic technical and chemical manuscripts is still in its preliminary stages, and it is too early to come to definite conclusions about water-cooling in Muslim alchemy”

Let us think carefully about this. First of all, su questo argomento devo avvalermi di fonti secondarie, come Forbes e gli altri sopracitati, dato che non conosco l’arabo. Premesso questo, we must never forget how difficult and laborious it was in the past to solve technical and scientific problems that appear quite straightforward to us, like the cooling of the still with water. Arabic chemistry and alchemy developed greatly over the centuries, while Western Europe was shrouded in its dark centuries. It is therefore reasonable to think that some Arab scientists managed to overcome the technical problems of the cooling process and to produce alcohol before it made its appearance in the West. But there is no evidence that it ever became a common technique, let alone a commercial production and consumption of Spirits.

The relation of Islam with alcohol has always been difficult. We know that the Quranic prohibition of consuming alcoholic beverages did not prevent many a group among the male elites of the Golden Age of Arab civilization from drinking wine. But surely this prohibition did not promote the creation of a social environment suited to the passage of alcohol – if they discovered it – from a scientist’s laboratory to a commercial distillery and then to the tables of a tavern. The very fact that today researchers have to look for evidence and corroboration of Arab alcoholic distillation in ancient, cryptic manuscripts half-forgotten in some ancient library, suggests that commercial production never developed. Otherwise, why didn’t it continue until today and even the memory has been lost?

To sum up, further studies may bring changes, but for now I feel I can safely say that the Arabs developed alchemy, chemistry and distillation and probably distilled alcohol too. But the production of alcohol, if even achieved, remained a limited experience, which never became commercial production and consumption of Spirits.