As I have already written, many today in the rum world seem to feel nostalgia for the good old times, when, in their opinion, the quality of rum (indeed, often the quality of quite everything) used to be better than it is now: more natural, authentic, artisan, and healthier too, a veritable Golden Age of Rum.

Unfortunately I have to disappoint them. Historical sources show us that, at least as regards rum, in truth there is nothing to be nostalgic for, and that the good old times were not so good after all. Obviously we can’t know exactly what rum tasted like in the past, but I think it can reasonably be said that it was generally bad, often disgusting and probably undrinkable for today’s taste. And in many cases it would be prohibited today by all the health authorities on the planet.

I haven’t done any dedicated research on the subject, simply I came across some interesting texts when researching for my books about the history of rum. Therefore I do not claim to make an organic speech about this issue (maybe in the future), I’ll just present some thought-provoking sources.

Let’s begin with the very first English and French ones, dating back to the 1600s

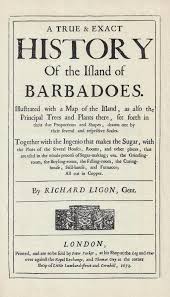

In 1647 Richard Ligon, a Cavalier, a Royalist, ruined by the Civil War, left England and sailed to Barbados to seek his fortune. He would spend 3 years there. He didn’t achieve what he had set out to do, so he had to go back to England, where things continued to go wrong for him, to such an extent that eventually he was imprisoned for debt. While in prison, he wrote a book on his journey, “A true and Exact History of the island of Barbados”, published in 1657.

Here is one famous excerpt from it.

“The seventh sort of drink is that we make of the skimming of sugar, which is infinitely strong, but not very pleasant in taste; it is common and therefore the less esteemed; the value of it is half a Crown a gallon, the people drink much of it, indeed too much; for it often lays them asleep on the ground, and that is accounted a very unwholesome lodging.”

Few years later, another much quoted English visitor to ( or settler in) Barbados described rum in the following, not exactly enthusiastic way: “the chief fuddling they make in the island is Rumbullion, alias Kill.Divil, and this is made from sugar cane distilled, a hot, hellish, and terrible liquor.”

At the end of the 1600s, the French Dominican priest Jean-Baptiste Labat, usually known in the rum world as Père Labat, volunteered to leave the convent for the colonies in order to replace deceased missionaries on Martinique. He wrote a big book about his experience “Noveau Voyage aux Isles de l’Amèrique …” (“New Voyage to the American islands ..”) published in 1722. Here are some excerpts

“The spirit we make on the Islands with mash & sugar syrups, it’s not one of the least used drinks, we call it Guildive or Taffia. The Savages, the Negros, the lowly settlers & craftsmen are not looking for another one & they lack self-control with this item, it is enough for them that this liquor is strong, violent & cheap; it doesn’t matter whether it’s harsh and unpleasant.”

“The spirits we pull from the canes are called Guildive. The Savages & the Negros call it Taffia, it is very strong, with an unpleasant smell & acridness, a little like grain-based spirits, which we have trouble taking away from them.”

In the second half of the 1700s rum became a widespread commodity. Consumers were well aware of the different geographic origins of rum, Jamaica, Barbados, Martinique, New England etc. and some rums were considered of far higher quality than others, with significantly different prices. In short, a proper international rum market already existed. Well, according to Guillame’s “Le Rhum sa Fabrication et sa Chimie”(1939) , in 1777 the “Encyclopédie” says:

“Rum is refined by distillers and traders who often blend a large quantity of low-priced liquor with coarse rum containing large quantities of essential oils which wipe out those of other fermented liquors. There is a lot of refinement in England. Some people are not ashamed to do this refinement with grain spirits or molasses. It’s very difficult to uncover this deception.”

At the end of the 1700s, John Bell served as a military surgeon in Jamaica. Back to England, in 1791 he published “An Inquiry into the causes which produce, and the means of preventing diseases …”. Bell was shocked by the mortality rate in the ranks “in some of those regiments, two thirds, and in others upward of a half, died, or were rendered unfit for service before they had been a year, or at most a year and a half, in the island of Jamaica.” In his opinion, the excessive daily consumption of rum was the primary cause of illness and death among the soldiers. The daily allowance was half a pint and was usually diluted with water, we do not know in what ratio. But soldiers bought much more undiluted rum, “large quantities of which of the most execrable quality” from private sellers at a cheap price. Actually, planters and distillers produced for the soldiers a kind of rum that only needed to be strong and cheap. It was fermented and distilled very quickly, saving on costs, without any regard for quality. As far as we know, the heads and the tails were not removed and in all likelihood in rum there was methanol, fused oils and bad congeners. And lead powder too, because lead and pewter were largely used in sugar and rum-making machinery. We know of soldiers who died immediately after they had drunk, or who fell to the ground in a state of torpor. Of hardy young men who declined rapidly. Of excruciating pains, ulcerated organs, illnesses …. The reports of the military surgeons of the time, and the first scientific post-mortems, tell us a terrifying story.

In the middle of the 1800s, France had become a major producer and consumer of rum. In 1864, the “Dictionnaire Francais” by B. Dupiney de Voupierre, writes:

“Under the names of Rum or Taffia, we designate two alcoholic liquors which are obtained from sugar cane; but the first is the product of the fermentation of molasses, a residue from the cane juice, while taffia is removed from the debris of sugar cane delivered to fermentation. Rum is naturally colourless and endowed with a flavour similar to that of the spirit, but it is given the golden colour and the particular flavour which pleases the consumer by infusing cloves, tobacco tar, and especially scraping of tanned leather; usually a little caramel is also added.”

Time goes by, but the quality of rum does not improve much. In his preface to Pairault’s “LE RHUM et sa fabrication”(1903) , Dr. A. Calmette, writes:

“It is enough that we protect it by an intelligent regulation which obliges the importers to definitively state the inconceivable fraud which consists of making a litre of authentic rum into three or four litres of a product sold under the same name. This product is a mixture of beet alcohols and wonderfully combined sauces to give the consumer the illusion of true rum perfumes. This fraud is not only detrimental to the interests of rum makers, it can also be harmful to consumers’ health.”

And now let’s read again some parts of the report of the “Royal Commission on Whiskey and other Potable Spirits”

Twenty-sixth day. Monday, July 20th, 1908.

Mr. Frank Litherland Teed, recalled

- Have you any reason to think that this imitation rum is being sold in this country? – I have no means of knowing. Of course, you might get the import numbers from the Customs, but I do not see how you are to get the quantities that are actually manufactured in this country. If you take the patent still grain spirit which I believe is now called patent still Scotch Whiskey, and put some of these ethers to it, it becomes rum. We have heard this morning that it becomes gin under certain circumstances, but, of course, if you put in other essences it may become brandy.

Twenty-seventh day. Tuesday, July 21st, 1908

Mr. James Monro Nicol, called

- You are exporters of Scotch whiskey, West Indian rum, British rum and compounded spirits, and you are proprietors of Customs bonded warehouses? – Yes.

- You wish to make some remarks to the Commission about a certain practice of mixing rum and plain spirit for exportation? – Yes.

- It has been suggested by one witness that this practice should be prohibited? – That is so.

- I understand that you take a different view: Will you kindly explain to the Commission exactly what that view is? – As stated in my précis, my present company and its predecessors have carried on that business for almost 40 years in accordance with the regulations of the Excise and Customs.

- That is the business of mixing Demerara rum with plain spirit in bond? – Yes. We therefore feel that it would be very unfair to us now to have that permission taken away not only on account of our own loss but we feel that it would be to the loss of the trade of the country, and there is no doubt about it that other countries would step in and do the trade if we did not do it.

- Under what designation is this mixed rum exported by you; how is it described? – It is ordered first of all from us as a rum and we invoice it as a rum. We use the term “rum” in our correspondence ourselves, but in the Customs, of course, the name “rum” is not recognised. The casks do not bear on them the name “rum”. They have to be marked “mixed”: That is certain.

- Not “rum” but “mixed” by itself? – Yes, the word “mixed”, which I suppose is a sufficient indication, or at least it meets the requirements of the Excise and Customs, that is a mixed spirit.

- That is, mixed for foreign use? – Yes.

- But is there any further mark on the cask that is exported? – That depends entirely on the market that the article goes to.

- Take Australia, for instance? – For Australia it is now necessary to add the country of origin on the casks and therefore they are marked: “The product of Great Britain and the West Indies”: There is no objection to putting on the word “British rum”, and as a matter of fact in exporting to Australia these two words do appear over and above the statement as the country of origin.

- You have on that cask when sent to Australia, have you not “British Rum”, the produce of Great Britain and the West Indies, in addition to the word “mixed”? – Yes, that is so.

- How do you invoice those mixtures? – It is invoiced as “rum”.

- Where does the bulk of that spirit go to? – It goes to Australia, New Zealand and the Australasian islands as well as to different parts of Eastern Europe.

- Would you regard that as a legitimate trade in this country? – I would.

- To sell that as “rum”? – Yes. I consider that there is no monopoly in the word “rum”.

- … What is the smallest amount of rum you can get in the cheapest article you send out? You must have a cheap trade as well as anybody else. What is the smallest amount of rum you would put in? – That we use, or that might be used?

- That you can put in? – I should say if you use one gallon of Demerara rum with your British spirit it would have to go out as mixed spirit.

- One gallon of Demerara rum to how many gallons of plain spirit? – One gallon of Demerara rum to 100 of plain spirit.

Mr. F.W. Percy Preston, called

- What is the nature of the business of your firm? – We are distillers and also exporters.

- Distillers of what? –What do you distill? – British plain spirit.

- Is that grain spirit? – Molasses spirit mostly. There is a little grain, but the bulk of our trade is molasses spirit.

- You are proprietors of Excise bonded warehouses? – Yes, and also of a vatting establishment over the top.

- You wish to give evidence before the Commission as the desirability or otherwise that the mixing of rum and plain spirit for exportation should be prohibited? – Yes.

- What do you wish to say in reference to that? – I simply say that if that is taken away from this country, the Germans take the trade and we lose it. They would send it direct from Hamburg to the West Coast of Africa, where I should otherwise send it, and they would simply take the trade off us, and our trade is ruined.

- What you export is a mixture of West Indian rum and British plain spirit? – Yes, made from molasses, which I call plain spirit.

- How do you invoice it? – It is really a trade term. A merchant writes to me and he says, “What is your price for African rum”, and I tell him what the price is. Another man from Manchester, from where most of the Mediterranean trade is done, writes and says, “What is the price for your Mediterranean rum”, and an Australian writes and says, “ What is your price for Australian rum”, and I tell them. The Excise know the proper thing to put on the cask. We do not work under the Customs, but we work under the Excise.

Finally, in 1946, D. Kervégant in his great book “Rhum et eaux-de-vie de canne” writes:

“Most countries, however, tolerate the sale, under the name fancy rum or imitation rum, of mixtures of natural rum and neutral alcohols, and even rum imitations obtained by merely adding the alcohols of dyestuff and aromatic compounds (improvers).”

I think this is enough. To sum up, the good old times of rum never existed and the Golden Age of rum is right now.

Marco Pierini

PS: It might be interesting to read carefully the rum labels of the past. I guess that few, if any, would comply with our contemporary requirements of transparency and education.

PPS: I published this article on December 2020 in the “Got Rum?” magazine. If you want to read my articles and to be constantly updated about the rum world, visit www.gotrum.com