In the first article of this new series dedicated to the role played by the French in the origins of rum, I published some documents according to which a commercial production of rum may have started in Saint-Christophe, Martinique and other French islands a few years before it did in Barbados. I hope to be able to publish other documents in the next articles.

But in order to understand historic documents properly it is not sufficient to just read them. We have to contextualize them, that is, put them in their proper historical period. In this case, we are referring to texts written in 1600s by French missionaries and travelers who wanted to tell about, and often actively promote, the colonization of the Caribbean. Both they and their readers were interested in American nature, the natives and their costumes, the new society arising on the islands and in the riches that could be amassed from those lands. The production of spirits was a matter of little interest to them and they gave it only scattered observations, not specific reflection.

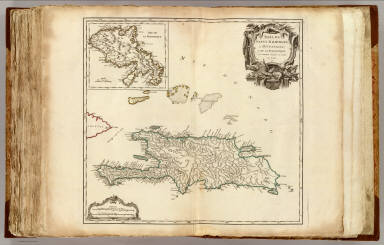

Let us say, yet again simplifying, that it is up to us to do some precise thinking. The first step is to understand how much the French knew about and how often they went to America in the 1620s and 1630s, at the time of their first permanent settlements in Saint-Chritophe, Martinica, Guadalupe etc.

Let’s see. In 1494, just two years after Columbus’ first voyage, Portugal and Spain signed the Treaty of Tordesillas under which the newly discovered lands would be divided between the two signatories. But France never accepted this Iberian monopoly and, from the very beginning, French seamen, merchants, privateers and pirates showed a keen awareness of the opportunities and wealth that could be derived from the new discoveries.

Later, after the Spanish conquest of Mexico and Peru, the sensational news of Aztec and Incan treasures whetted other European appetites, especially those of Spain’s enemies. First of all France, which was at war with the Spanish Empire for roughly all the first half of the 1500s. Wars are expensive. The fleets coming back from America loaded with treasure were vital to ensure the wealth and consequently the military power of the Spanish empire; for this reason the Spanish towns and ships of America became subject to constant attack by the French.

As Philip P. Boucher writes in his seminal work FRANCE AND THE AMERICAN TROPICS TO 1700, “The French king François I (r. 1516 – 1547) vociferously refused to honor Iberian pretension to monopoly on America. In an oft-quoted anecdote, he reputedly asked the Spanish ambassador to produce Adam’s will leaving the Americas to Iberians. He insisted that legitimate claims to areas overseas depended on de facto occupation, not on grandiose papal grants. … Not only did François support voyages searching for a northwest passage to the Orient, the expeditions of Giovanni da Verrazzano, Jacques Cartier, and Jean Roberval, but during these years of almost continuous war, he unleashed privateers in the Caribbean.”

French privateer attacks achieved spectacular success, one of the earliest being the 1523 capture of Spanish ships carrying the stolen treasures of the Aztec city Tenochtitlan off the coast of the Azores by Jean d’Ango, a wealthy ship owner from Dieppe. Later, in 1555, the French privateer Jacques de Sores captured Havana and burned it to the ground. Only the terrible religious and civil wars that tore apart and bled France dry in the second half of 1500s prevented the French Crown from establishing enduring colonies in America.

This it enough for the French connection with America in general; now let’s focus on Brazil, which roughly from 1550s to 1650s was the biggest producer of sugar in the West world.

French captain Binot Paulmier de Gonneville, in 1504 onboard L’Espoir, visited Brazil and traded with the natives. He also brought back to France a Native American person named Essomericq. Gonneville stated that when he visited Brazil, French traders from Saint-Malo and Dieppe had already been trading there for several years.

We know from contemporary sources that from the very beginning of the settlement, the Portuguese were worried about the presence in Brazil of other Europeans, first of all the French. Let me quote Schwartz, S.B. EARLY BRAZIL. A DOCUMENTARY COLLECTION TO 1700: “The Portuguese Crown made efforts to clear foreign competitors, especially Norman and Breton ships, from the coast, and to that end Martin Alonso de Sousa captained an expedition in 1532 that sought to ensure Portugal’s control of the new land.”

France continued to trade with Portugal, especially loading Brazil wood, for its use as a red dye for textiles. The fascination that Brazil and its inhabitants exerted on the French was very strong, to the point that in 1550, during the great celebrations for the royal entry of King Henry II at Rouen, about fifty men disguised as naked Brazilian natives staged a battle between the Tupinamba allies of the French and their enemies, the Tabajaras.

The French ambitions on Brazil were not limited to trade, they also tried to colonize it.

The first French settlement in Brazil was called France Antartique. In 1555, French vice-admiral Nicolas Durand de Villegaignon, a Catholic knight of the Order of Malta, led a small fleet of two ships and 600 soldiers and colonists, and took possession of the small island of Serigipe in the Guanabara Bay, in front of present-day Rio de Janeiro, where they built a fort. In 1560 Mem de Sá, the new Governor-General of Brazil, received from the Portuguese government the order to expel the French. With a large fleet he attacked the French colony. The strong religious tensions that existed, in the colony and at home, between French Protestants and Catholics, weakened the defense and delayed the dispatch of reinforcements from France. In January 1567, the Portuguese inflicted a final defeat on the French forces and decisively expelled them from Brazil. In the place, the Portuguese founded the city of Rio de Janeiro.

A second settlement was France Équinoxiale, started in 1612, when a French expedition departed from France, carrying 500 colonists. They arrived in the Northern coast of what is today the Brazilian state of Maranhão where they soon founded a village, which was named “Saint-Louis”, in honor of the French king Louis IX. The colony did not last long: a Portuguese army defeated and expelled the French colonists in 1615. A few years later, in 1620, Portuguese and Brazilian colonists arrived in number and São Luís started to develop, with an economy based mostly on sugar cane and slavery. Actually, it was largely in response to the attempts of France to trade with the natives and to conquer new territories that the Portuguese crown decided to expand its colonization efforts in Brazil.

French traders and colonists tried again to found a colony further North, in what is today French Guyana, in 1626, 1635 and 1643. It was only after 1674, when the colony came under the direct control of the French crown and a competent Governor took office, that France Équinoxiale became a reality. To this day, French Guyana is a department of France.

To sum up, according to W.J. Eccles in his THE FRENCH IN NORTH AMERICA, “For a century, French traders had challenged the Portuguese hold of this vast region, with little or no aid from the Crown. But for the religious dissensions at Rio de Janeiro, and the unfortunate character of Villegaignon, France rather than Portugal might have established a vast empire in South America.”

Therefore, in the 1620s and 1630s, when the French began to settle in the Caribbean, they knew America and its resources well. In particular, they had a long experience of travelling to and trading with Brazil, a great producer of sugar and where, at least from the beginning of 1600s, rum was produced too. This part of the historic context of our documents is sufficiently clear.

What remains to be seen now is whether the French already knew alcoholic distillation, sugarcane cultivation and sugar making.

See you again in the next issues.

Marco Pierini

PS: I published this article on december 2018 in the “Got Rum?” magazine. If you want to read my articles and to be constantly updated about the rum world, visit www.gotrum.com

My husband and i felt absolutely satisfied Ervin could conclude his inquiry through the precious recommendations he obtained through the blog. It’s not at all simplistic just to be making a gift of key points which the rest might have been trying to sell. And we also figure out we have got you to thank because of that. Most of the illustrations you’ve made, the simple website navigation, the relationships you make it possible to foster – it’s many extraordinary, and it’s helping our son and us believe that this theme is brilliant, and that is truly fundamental. Many thanks for all the pieces!

Can you explain – Adam’s Will.

Dear Luis, this is the part of the article explaining why Adam’s Will: As Philip P. Boucher writes in his seminal work FRANCE AND THE AMERICAN TROPICS TO 1700, “The French king François I (r. 1516 – 1547) vociferously refused to honor Iberian pretension to monopoly on America. In an oft-quoted anecdote, he reputedly asked the Spanish ambassador to produce ADAM’s WILL leaving the Americas to Iberians. He insisted that legitimate claims to areas overseas depended on de facto occupation, not on grandiose papal grants. … Not only did François support voyages searching for a northwest passage to the Orient, the expeditions of Giovanni da Verrazzano, Jacques Cartier, and Jean Roberval, but during these years of almost continuous war, he unleashed privateers in the Caribbean.”