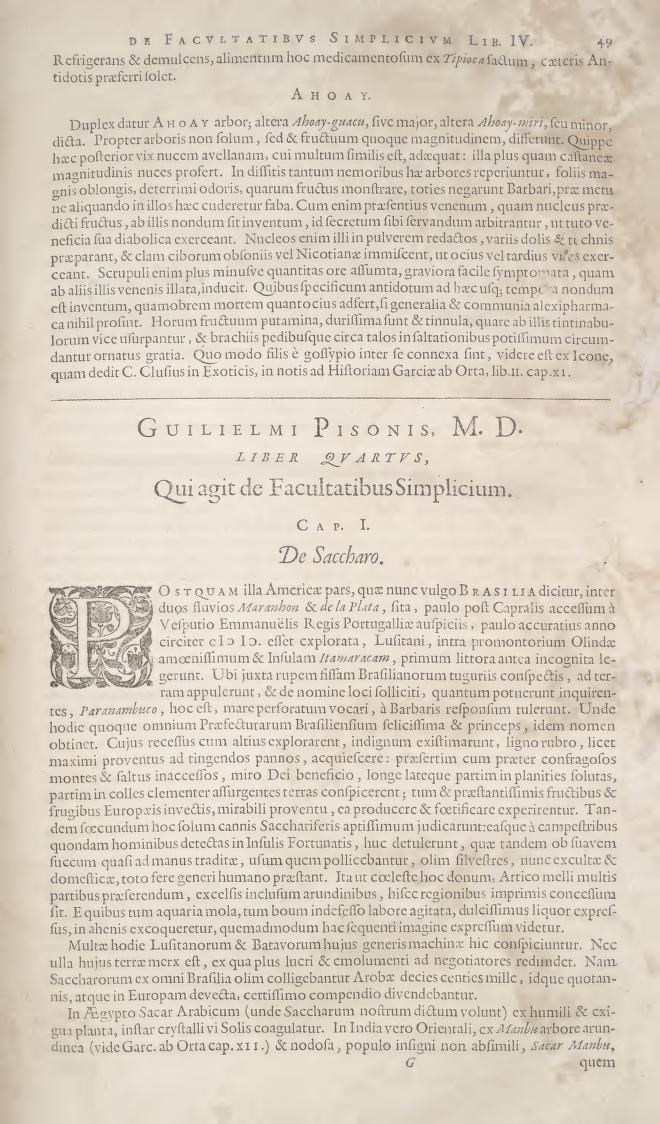

“Historia Naturalis Brasiliae” devotes a whole chapter, written by Willem Piso, to sugar. Hardly surprising, since the Dutch had gone to Brazil mainly to take hold of its precious sugar. But, like many of his contemporaries, Piso is also struck by the complexity and sheer spectacle of sugar making. At the time in Europe there were hardly any big factories. Manufacturing took place in many small workshops where often a singlemasterworked leisurely, assisted by few apprentices. In sugar factories, on the other hand, during the harvest, “night and day tongues of fire rise up, terrible in their blaze”, around which scores of black, half-naked, sweating men bustle in a frenzied way. The sugarcane is unloaded from the carts, cleaned, cut and squeezed. And the juice gathered is boiled in the cauldrons. All in quick, rigorous succession and hurriedly, breathlessly … a hellish scene, a veritable Tropical Babylon, as a contemporary wrote.

Piso had to understand what he saw, then he had to explain it to his European readers. And explain it in Latin. But the ancient Romans, whose language he wrote in, did not use sugarcane, sugar factories, sugar, stills, distillation or spirits. It was therefore necessary tointroduce new words into Latin, such as caldo for the juice of the cane. Or bend old words, born in an entirely different context, to make them express a new meaning; so, vinum, wine, becomes a general term for every fermented beverage.

After describing how sugarcane was squeezed and the caldo collected, Piso writes: “Thence, mixing some water with it, they make also a wine, popularly called Garapo: local people ask for it greedily and on it, if it is aged, they get drunk.” So far, nothing new: we already knew that a fermented beverage obtained from sugarcane, here called Garapo, had been widely drunk in Brazil, for more than a century, by slaves, natives and poor white people. What additional information Piso gives us is that, sometimes, it was deliberately aged. But why? Did its quality improve through ageing? I don’t understand, I would entreat all of you to enlighten me.

He then goes on:

“So, from this first liquid [that is, the caldo], sugary wine, vinum adustum, acetum, cooked honey and sugar itself can be prepared.”

Let us give a good look at this list. Sugary wine isGarapo. Acetum is raw juice mixed with water, after a few days it went sour and was used in medicine. Cooked sugar is molasses. And sugar is sugar.

So, what is vinum adustum? The literal translation is “burnt wine”. Evidently, another beverage, besides Garapo, was obtained from sugarcane. A beverage which was made by burning the Garapo itself. And maybe this is what Piso refers to when he writes “and on it, if it is aged, they get drunk.”

But in the Piso’s Netherlands a burnt wine was already widespread. It was made by burning, that is, distilling the wine made from grape juice and it was extremely strong. It was called gebrande wijn, which means, more or less, burnt wine. Better known as Brandy.

Piso must bend his Latin to describe something which in Latin did not exist and which is similar to Brandy. He is telling us that the fermented cane juice was then burnt, that is, distilled in a still, as they did for Brandy, resulting in a strong new beverage.

He does not have a specific name for it yet and, basing himself on the production process, calls it vinum adustum, burnt wine. But now we can call it by its real name: Rum.

Marco Pierini

PS: I published this article on August 2015 in the “Got Rum?” magazine. If you want to read my articles and to be constantly updated about the rum world, visit www.gotrum.com

Thanks for conveying this particular article and making it public

I included this write-up to my book marks

Came across this write-up curious, added to meemi

Located this blog post interested, added to diigo