In the middle of the XVII° century, rum starts from Barbados (and Martinique) its long, victorious march to conquer the world. A world which was very different from today’s, and where sugar was a source of enormous wealth and the cause of bloody wars and, leaving aside Portuguese Brazil because of its relative isolation, the heart of sugar production was in the Caribbean. In those years and for about one century, three great colonial Empires divide up most of the Americas.

the Americas.

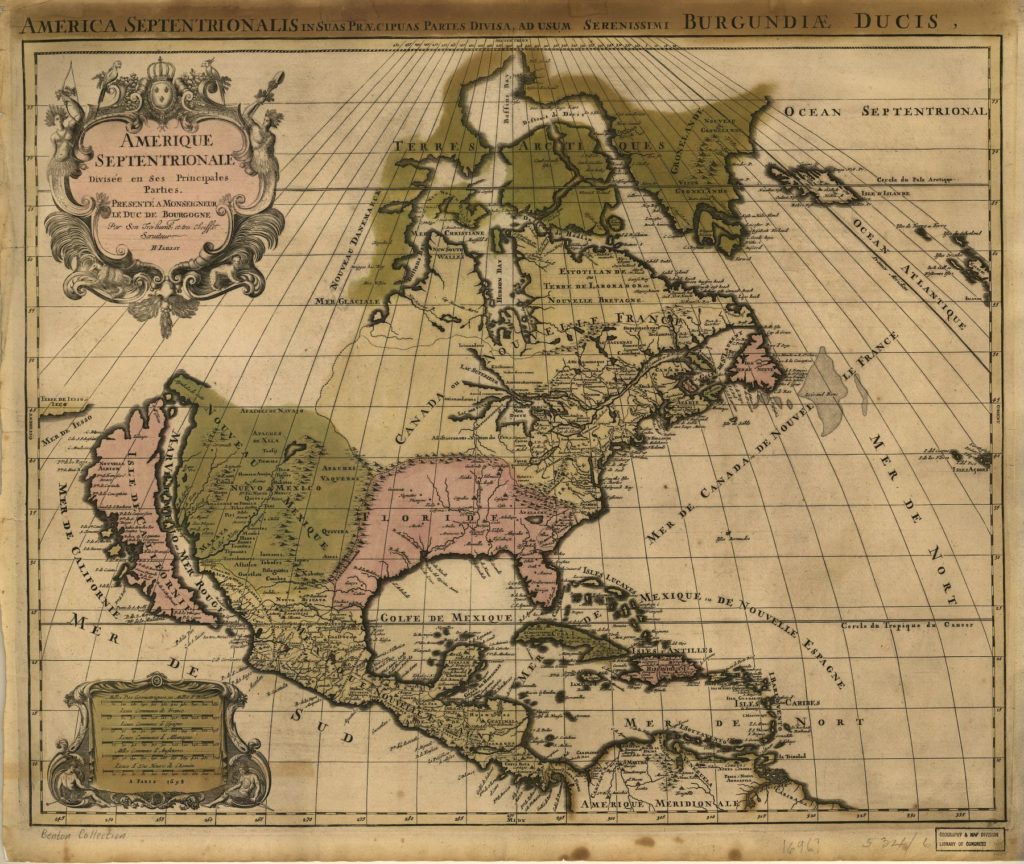

To put it simply, the Spanish Empire dominated Central and South America Mainland and the main islands, Cuba, Portorico, part of Santo Domingo. The French Empire keeps Martinique, Guadalupe, other smaller islands and part of Santo Domingo (now Haiti) under its tight control. The English (later British) Empire has long occupied Barbados and other smaller islands, and in 1655 it succeeds in wresting the great island of Jamaica from the Spanish. In the Caribbean, sugarcane could grow everywhere, therefore rum could be produced everywhere. But the choices of the three European countries were completely different (A warning: we use the word rum, but our spirit was called with many di fferent names).

fferent names).

Spain was a major producer of wine and brandy. A significant part of this production was exported to the Spanish colonies in America and to Northern European countries, among which England. The Spanish producers of wine and brandy saw rum as a threat to their interests and got the government to discourage the production of alcoholic beverages in the colonies with all the means at its disposal. Bans on growing grapes, bans on the sale of alcoholic beverages to the natives, prohibition to sell local alcoholic beverages in the towns, and so on. Over time, a long succession of laws were introduced, which forbade distillation, with the most brutal punishments. These laws were not always fully enforced (through and through), but they negatively affected the development of rum production. To this we must add the decline of sugar production, which has not yet been fully explained by historians, and a diminished fondness of Spanish people for strong distilled beverages. As a result, rum (moonshine) production in the Spanish colonies was reserved, for a long time, only to local markets and it was of low quality.

France too was a great producer and exporter of wine and brandy and French producers too feared the competition of rum. But things went differently. I have not yet studied this issue as it deserves, but in the second half of the XVII° century there was an extensive rum production right in France, by using the syrups which were the by-product of the refining of Antillean sugar, which took place largely in France. Then, brandy producers struck back with various bans and restrictions and in 1713 they even obtained a Royal Decree which forbade the use of any raw material other than wine for the distillation of spirits. It seems that after 1713 rum production and sale were really forbidden in France, but de facto tolerated in the colonies. Moreover, in the French Antilles sugar production was thriving and the French were fonder of strong liquors than were the Spanish. To sum up, rum production in the French Antilles was always significant.

In England, vines did not grow and it was impossible to produce wine and brandy. On the other hand, English people drank heavily, they had always done. They imported wine and brandy mainly from France and Spain. And they paid good money for them. It was a constant flow of wealth which left the English shores to boost the coffers of foreign countries. For centuries it had not been considered a problem or anyway maybe there were no solutions. But things change. After the 1650, England/Great Britain was one of the great European and world powers. Its foreign policy had two fundamental objectives: to strengthen its global role, by defending and expanding its colonial, commercial empire, and at the same time to maintain the balance of power in Europe, in order to prevent a single country from becoming so strong as to dominate the continent. (Maybe, it may be thought that this general approach underlines British foreign policy even today). Both objectives brought England/Britain to fight many wars and especially to clash with France, its only real competitor in the struggle for the world supremacy. It became therefore intolerable to finance the enemy through imports of wine and brandy.

A solution for wine was soon found: trade agreements were signed with neutral Portugal to import its sweet wines. Moreover, instead of forbidding or limiting the production and exports of rum, the British government promoted them carefully. The British Empire quickly became the first producer and consumer of rum in the world, soon rum was considered everywhere as something typically British and even now it is the English word rum ( of uncertain origin) by which our spirit is known almost all over the world.